There is a tendency to think of native strips or verges as just another form of public greenspace like parks and community gardens. And a less important one, at that.

But this space – between the front property line and the road – has some special features that set it apart from other public land.

A standard barren footpath, street tree, footpath, cut low with edges trimmed.

A standard barren footpath, street tree, footpath, cut low with edges trimmed.

These features can create both conflict and opportunity.

- It has a complex ownership and shared responsibility – a public space that is ruled by councils but largely maintained by residents

- It may include street trees and concrete pathways installed and maintained by councils

- Pathways through verges and nature strips are pedestrian thoroughfares and play a vital role in the encouragement of walking and public transport

- This area houses many underground services which means it must be accessible to workers and may be dug up without notice

- The postie, often on a motorbike, and others need access to the letter box

- Some verges include bus stops

- It is a buffer zone between private gardens and public drains, creeks and remnant bushland

- Cars are often parked alongside the kerb and sometimes illegally on, or half on, the verge

- It is the place where we cross from our private world into the public realm, from resident to citizen

Councils have historically avoided much of the conflict by demanding ubiquitous grass verges that residents are usually obliged to mow.

However, many councils are now producing policies and guidelines for residents to replace the grass on their verge with low growing plants to create more diverse nature strips.

A few councils actively promote this planting as part of their strategy to increase shade and environmental biodiversity.

Conflict on the Verge

The complexity of public attitudes towards verges becomes apparent when there is a dispute.

Cars parking on the verge and across driveways, neglected weedy verges, verges blocked so pedestrians must walk on the road, dogs owners not picking up after their pets, are common gripes.

There are more subtle, unspoken rules too.

Some people object to strangers congregating on the footpath in front of their house, or consider any kerbside parking in front of their house as being for themselves and their visitors to use, and are annoyed by neighbours or strangers parking there.

Flat and green, or flat and brown in a dry summer, is ok. Weeds are ok if they are mown like grass. As long as it is neat enough and doesn’t draw attention as you drive by in a car.

This is what passes for turf at my local bus stop. Maintained by council mowing contractors, it is more weed than grass. No conflict or opportunity here.

This is what passes for turf at my local bus stop. Maintained by council mowing contractors, it is more weed than grass. No conflict or opportunity here.

Councils have long cited public liability as the reason for not allowing anything other than standard grass verges. Allowing grass only is an easy way out of that.

Several years ago, some streets at Buderim on the Sunshine Coast became known as the Urban Food Street. Many residents participated growing food on the verges, until the Sunshine Coast Council removed the fruit trees from verges in 2017.

A complaint had been made, councils are obliged to act on complaints, negotiations broke down, the council enforced their laws.

It was a public relations disaster for the council, the end of the Urban Food Street, and nobody was the winner. This is not an outcome I wanted for my verge, or want for any Shady Lanes Project.

Approaching my planted verge garden with a young street tree planted by Council. In the foreground is the neighbour’s standard mowed verge. Council footpath runs through. This verge complies with current Brisbane City Council policy.

Approaching my planted verge garden with a young street tree planted by Council. In the foreground is the neighbour’s standard mowed verge. Council footpath runs through. This verge complies with current Brisbane City Council policy.

My own verge garden is three years old (in 2020) and I’ve had many conversations with neighbours and pedestrians while weeding or watering the verge over these years. Reactions have been varied but positive, although I believe that is largely because of the design and type of plants. I don’t think an Urban Food Street style garden would have been accepted so well in my suburban street.

Paper Daisies have received more positive comments than any other plant. It’s not unusual to see butterflies and native bees on the flowers. Some people have told me they like to see the changes in flowers through the seasons.

Paper Daisies have received more positive comments than any other plant. It’s not unusual to see butterflies and native bees on the flowers. Some people have told me they like to see the changes in flowers through the seasons.

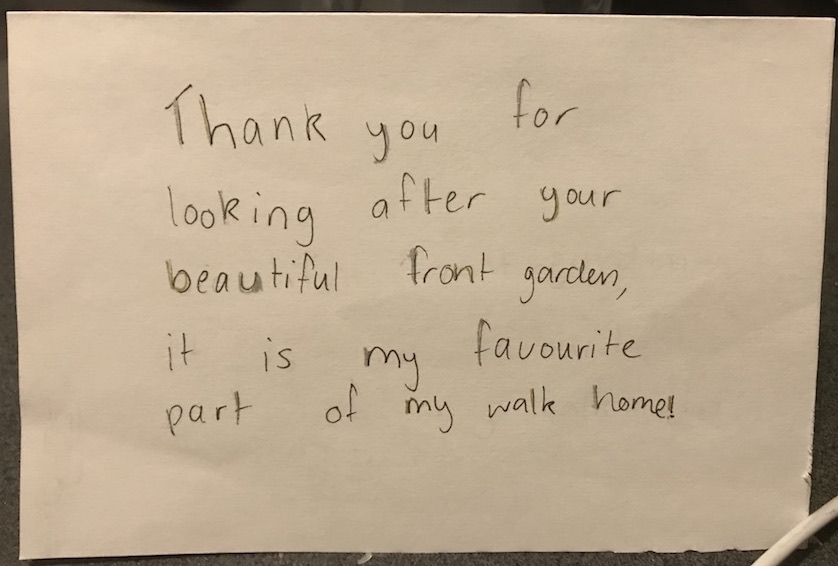

Through these discussions, I’ve come to realise that the key to acceptance of verge gardens is to maintain the feeling of fairness.

If people feel that you are taking over public land for your own purposes, it can bother them. If it impinges on their ability to walk comfortably down a street on the footpath, it can make them more angry every time they pass. Maybe just a bit at first, but more over time.

That is why planting a lush food forest, yukkas that poke at pedestrians, vines that get caught in the wheelchair or pram wheels, or using the verge as a car park often leads to conflict and disputes.

Opportunity

The other side of side of the fairness coin is that your verge garden is contributing to the general community. You are making it better (cooler, more attractive, more interesting) for everyone. You are not demanding anything of them and not trying to draw them into your desired community of urban farmers but allowing them to enjoy it on their own terms.

Anonymous message inside a hand-made card found in my letterbox.

Anonymous message inside a hand-made card found in my letterbox.

This is not an easy line to navigate, either for the councils or the individual residents. But if you do manage it, keeping in mind the need to engage (or at least not upset) all stakeholders, the opportunities and rewards are worth it.

And there are many opportunities, rewards, and stakeholders.

Here are some of the benefits:

- resident-maintained naturestrips support the health of street trees at no cost to council

- increasing tree canopy in cities helps tackle the urban heat island effect, cooling the suburbs and reducing air-conditioning bills

- more diverse habitat for native wildlife and pollinators

- opportunities for city dwellers to engage with nature close to home, giving physical and mental health benefits

- cooler and more pleasant walkways encourage active transport, giving health benefits and reducing emissions

- reduction in greenwaste and emissions from mowers

- reducing rainwater runoff from urban areas into the stormwater system

- improving the soil health and sequestering some carbon

The unique features of the street verges bring it all together – shared responsibility, active citizenship, multiple goals, breaking down the “it’s someone else’s responsibility” attitude encouraged by hierarchical and siloed thinking into what can each one of us can do in a collaborative, open and localised manner.

The Private/Public Interface

Looking at the list of special features of verges above, it is the last one – It is the place where we cross from our private world into the public realm, from resident to citizen – that highlights perhaps the greatest opportunities and benefits presented by these neglected patches of land.

Unlike a park that we might choose to visit, the street verges are part of our daily lives. We walk out of our front gate into them, we drive across them or walk through them every time we go out.

As a resident responsible for the maintenance of that little patch of land, or a driver looking for a car park, a person walking their dog, we choose whether to behave as an engaged citizen who considers their actions on others, or as a simple consumer of public resources.

Shady Lanes takes Verge Gardening a step further

Until now verge planting has remained the realm of gardening enthusiasts who have the time, ability and confidence to plant the gardens.

But not everyone is a gardener, not everyone has the time, resources, physical ability, or the interest to convert their verge into a garden.

The aim of the Shady Lanes Project is to extend verge garden planting throughout the suburbs, especially to disadvantaged suburbs where unemployment is entrenched and residents are already being hit hardest by rising urban heat.

We can do this by bringing together the multiple stakeholders, and multiple goals, to create collaborations with a range of opportunities for funding managed projects to do the initial conversion.

The added benefits of doing this are…

- local employment opportunities through social enterprises and small businesses to do the initial conversions from grass to garden

- building connections within communities – between many stakeholders

Being public land, accessible to everyone, makes applications for funding or sponsorship to cover the initial transformation from grass to planting possible in a way that wouldn’t be appropriate inside private gardens, or even for community gardens where benefits are restricted to members.

Engaging social enterprises and their workers to complete the conversions adds more stakeholders and funding options.

Clubs, service organisations, and community leaders have a ready-made framework to apply for funding projects to benefit their communities.

Ongoing Maintenance

“But who’s going to look after them?” is the other common question you hear in discussions about verge gardens.

The simple answer is the two stakeholders who currently maintain the verges. The councils will continue to plant and prune the street trees. The residents provide water for young trees and tend to the understory garden – which is less work than mowing and edging.

Stakeholder management by a local project leader smooths this transition. Residents need to be brought together as a community to be part of the process, having a say in the layout and planting of the understory, within the council policy guidelines. They have to be able to opt out, or agree between them to adopt an uninterested neighbour’s verge.

Takeaways

- The unique features of this public land is what provides the impetus to engage many stakeholders to work collaboratively.

- Projects fit in with existing goals and responsibilities of stakeholders, the change is in the collaborative relationships built.

- Projects continue to evolve after the initial transformation. Individual residents may come and go – the trees and gardens live on.

- Restricting planting to street trees and predominantly low-maintenance, water-wise, native habitat reduces risk of disputes.

- Every project must be localised with a local leader, and local organisations to ensure participation and adoption by the community.

Over to You

Can you pull these pieces together in your local area?

- a street in your area that would benefit from a conversion

- resident gardeners who will volunteer, or a local NFP organisation who would seek funding, or a business that would sponsor the conversion work

- a local social enterprise or small business who would do the conversion if you have funds

- a community nursery that would provide tubestock and advice

- the council which provides the policy, planting guidelines, and plants the street trees

Start with the free course, Verge Garden Basics – Understanding the Space about understanding the complexities of gardening on our streets and an introduction to planting as advocacy and collaboration.